A pioneering initiative ensures every Tar Heel student has free access to powerful digital tools — and the coursework that teaches them to be critical thinkers and sophisticated users of essential technologies

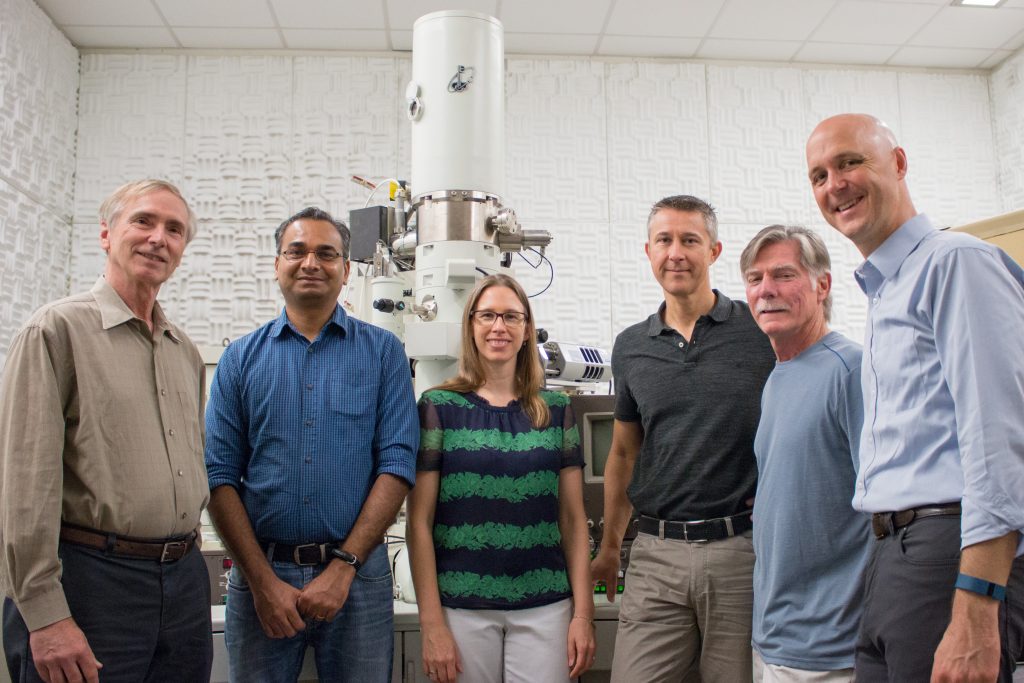

Dan Anderson, left, director of UNC’s Digital Innovation Lab, and Todd Taylor, director of the Writing Program, teach a hands-on workshop for English 105 instructors at the start of the fall semester. The session focused on how to design digital class projects. (photo by Donn Young)

To describe students in 2017 as digital natives is stating the obvious, but what is not obvious is where they sit on the continuum from passive consumers of digital media to experienced producers of compelling content.

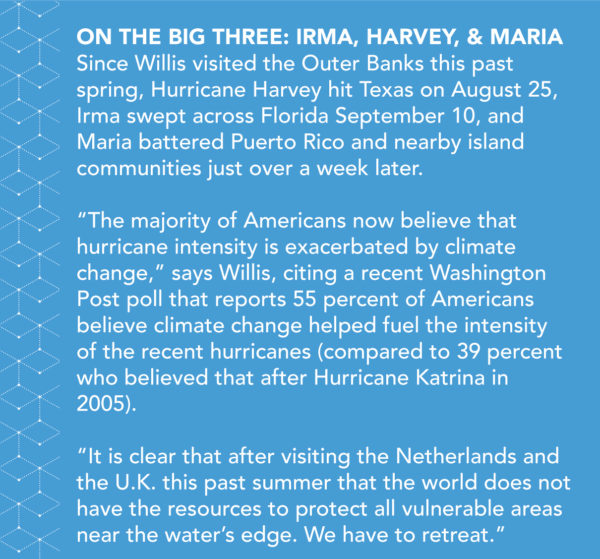

Starting this fall, as part of a larger College of Arts & Sciences goal to ensure that future Tar Heels graduate with a high degree of digital literacy, a required English course will include at least one major digital project. At the same time, all students will have free access to powerful digital tools, thanks to an extraordinary partnership between UNC and a major software provider.

Planners envision that this digital project will be the start of an “e-portfolio” that students will build throughout their years at Carolina to showcase their scholarship and digital skills.

These efforts are part of the ambitious Carolina Digital Literacy initiative, which has its roots in an earlier historic first: In 2000, when UNC began requiring that every student have a laptop, it also ensured access for all by providing grants to cover the cost for students who couldn’t afford one. That approach was believed to be unique among public universities requiring students to have computers.

“Other schools may be offering free software to students, but we’re saying digital literacy is an essential skill that doesn’t belong to any corner of the curriculum; it will be across the curriculum,” says Todd Taylor. (photo by Donn Young)

In 2016, the University announced that it had paired with Adobe Systems to provide all students and faculty with free access to the Creative Cloud suite of software (which includes such design mainstays as Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign and Dreamweaver). An individual student license normally costs upwards of $240 a year.

Todd Taylor, director of the UNC Writing Program and professor of English and comparative literature, and who has been teaching digital media courses at Carolina for more than a decade, said he is unaware of any other university embarking on a digital initiative that approaches the scope of Carolina’s.

“Other schools may be offering free software to students, but we’re saying digital literacy is an essential skill that doesn’t belong to any corner of the curriculum; it will be across the curriculum. Such a strategic implementation that begins with early exposure in this required course is what makes us different from any other campus,” he said.

From functional to critical literacy

The course at the heart of this digital revolution is English 105: “English Composition and Rhetoric.” This writing class is required of every single undergraduate at UNC-Chapel Hill. That’s at least 120 sections offered each semester (capped at 19 students per class), as more than 4,700 first-year and transfer students complete this core experience annually.

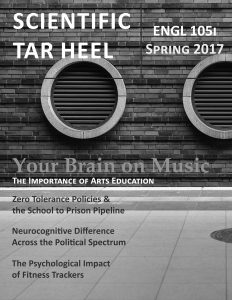

Students in one class created a Scientific American-like popular magazine as a digital project. (courtesy of Tiffany Friedman)

Requiring every section of English 105 to include a digital component “may sound ambitious, but probably two-thirds of the classes were already doing a digital project,” said Dan Anderson, director of the Digital Innovation Lab and a professor of English and comparative literature.

Anderson, for one, finds the term “digital literacy” limiting. He expects Carolina to go far beyond “functional literacy” — knowing how to use software to design a poster, create a video, or launch a website, for example.

“I want students to have ‘critical literacy’— to not only be able to communicate with these tools but to step back and analyze culture and meaning,” he said.

Both Anderson and Taylor emphasize that there are numerous digital tools beyond the Adobe offerings, and that English 105 instructors are using a panoply of approaches to help students develop digital proficiencies — from working with data to media production to critiquing and developing social media campaigns.

“One part of digital literacy is knowing what tool to choose and how knowledge is shaped and shared by a range of activities,” said Anderson.

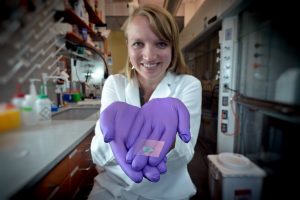

An example of an English 105 digital project is Scientific Tar Heel, an assignment created by instructor Tiffany Friedman.

In the science writing unit of the class, Friedman asked her students to research and write an article that might appear in a magazine like Scientific American. However, they didn’t just turn in a typed manuscript. They used magazine design software to lay out the articles, photos, tables and other graphics. That showed them how elements such as font choice and photo selection shape a reader’s perception of the story. They knew the finished product would be shared online, which upped the stakes for quality. (See an issue at cdl.unc.edu/assignments).

Other English 105 projects have included preparing short service-learning films or audio e-poems.

“I want students to have ‘critical literacy’— to not only be able to communicate with these tools but to step back and analyze culture and meaning,” says Dan Anderson. (photo by Donn Young)

Focus is on the words

For those who wonder why students in a “writing” course are making films, Taylor responds: “I don’t know of a film — including every Hollywood blockbuster — that doesn’t start with a script. During the editing process, you’re paying incredibly close attention to the narrative. The focus is on the words. And then you work with the visuals to illustrate that.”

A recent graduate of Carolina who took one of Taylor’s multimedia composition courses echoes his sentiments.

“One of the cool things for me in working with film is I had to strip it down to the essence,” said Izzy Pinheiro (interdisciplinary studies ’17), who created a documentary for class about using music and art to help people cope with illness. “I had to go over the material over and over again. You think about the audience and how it all fits together.”

Pinheiro received a grant to travel to Jordan last summer to make a film on Syrian refugees. She plans to launch a career in human rights work.

An important partner in the digital literacy initiative is University Libraries. Media Resources Center staff have been working with instructors as they develop their assignments; they are a resource for students as well.

“The instructor might assign something, and we will ask, ‘What is your learning goal here?’ said Winifred Metz, who heads the Media Resources Center. “We match them to the best tool for the assignment, whether it is a podcast, TEDx Talk or infographic. Not only do we provide instruction on the software, we show them how to use the hardware — the camera, the audio recorders, how to download the clips to edit. We walk them through the whole process.”

College Dean Kevin Guskiewicz, Chancellor Carol Folt and Provost Jim Dean were early champions of the initiative, said Chris Kielt, vice chancellor for information technology and one of the drivers behind the Carolina Digital Literacy Initiative. In addition to Kielt’s office, the College and University Libraries, the School of Media and Journalism and other units across campus are partners in the digital effort.

As part of the software partnership, “we asked faculty to tell us how they were using digital tools in their classrooms,” Kielt said. “They are being used in courses like religious studies and biology and nursing, and yes, of course journalism and communication and English. It’s being used across the curriculum. This has been one of the most satisfying experiences in my 30 years of higher education.”

By Geneva Collins

——-

——-