An art historian, a costume designer, a math biologist, a biomedical engineer and a team of undergraduate researchers unite to reimagine a breathtaking 9th-century flying experiment — and make a notable contribution to early aviation history.

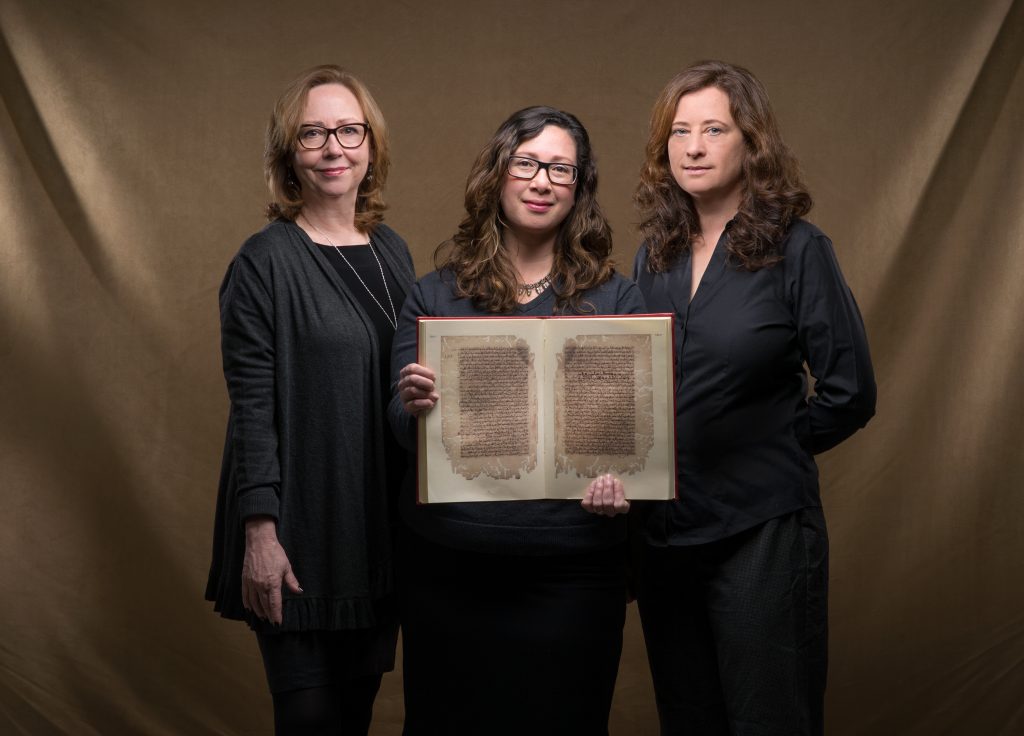

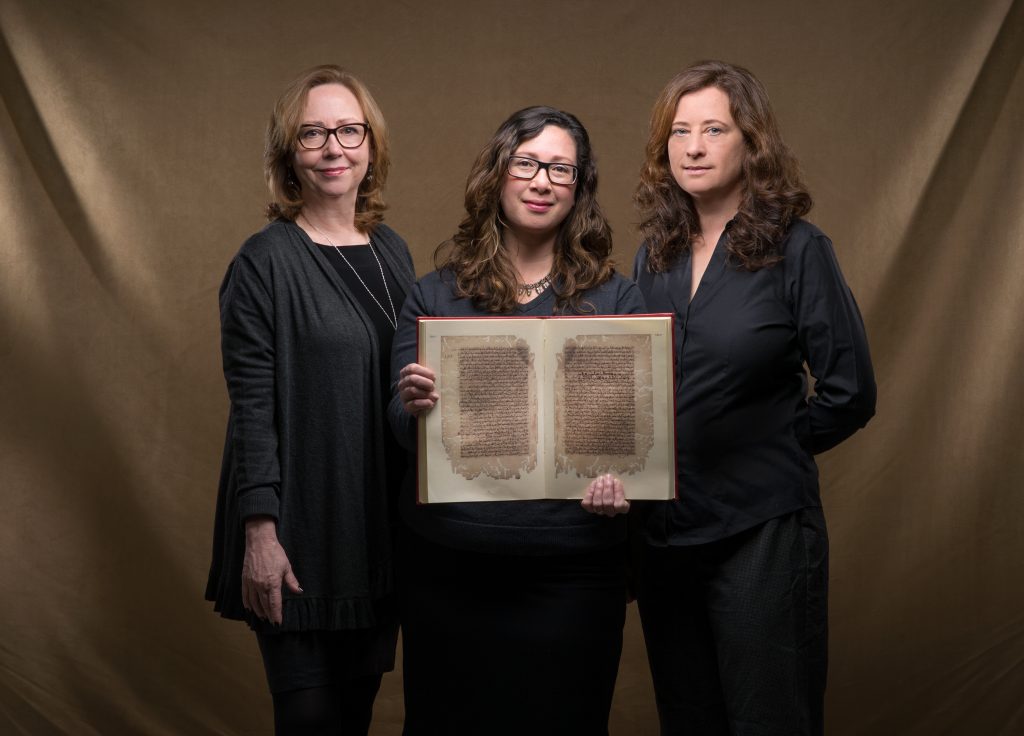

Jan Chambers, Glaire Anderson and Laura Miller hold a facsimile of an 11th-century Arabic manuscript describing the flight of inventor Abbas ibn Firnas. “The manuscript has yet to be incorporated into scholarship on aviation history,” said Anderson. (photo by Steve Exum)

More than 1,000 years before the Wright brothers made their historic flight over Kitty Hawk, and 600 years before Leonardo da Vinci sketched out a mechanical flying machine, an Islamic inventor named Abbas ibn Firnas designed a winged device, dared to test it himself and … flew.

Glided, to be more precise. According to the earliest historical account, he rose, moved through the air, circled and landed far from his launching point, hurting his tailbone in the landing.

Glaire Anderson knew of Abbas ibn Firnas and the accounts of his flight. The associate professor of art history specializes in early/medieval Islamic art and architecture. Although Ibn Firnas is not well known in Western culture, he is a staple of Islamic history books. His achievements have been recognized by NASA; a crater on the moon bears his name.

Attending a dinner for newly tenured faculty in 2013 and describing her research to colleagues, she mused about what a 9th-century flying apparatus might look like.

“You need a costume designer,” said her tablemate, Jan Chambers, associate professor of dramatic art and resident designer for PlayMakers Repertory Company.

A collaboration began to take form, one requiring both art and science. The goal was twofold: (1) to create an artistic interpretation of Ibn Firnas’ glider wings and garment that reflected the history, culture and technology of the time, and (2) to provide a means for students to think about the problems of early human flight by testing the fanciful device’s aerodynamic capabilities in UNC’s Joint Applied Math and Marine Sciences Fluids Lab. [Read more about the fluids lab].

The team grew to include Laura Miller, associate professor of biology and mathematics, who studies flight as part of her fluid dynamics research; Julia Kimbell, a research associate professor in the School of Medicine and an adjunct in biomedical engineering, and several undergraduate research associates, including two students in the Computational Astronomy and Physics Research Experiences for Undergraduates program, or CAP/REU.

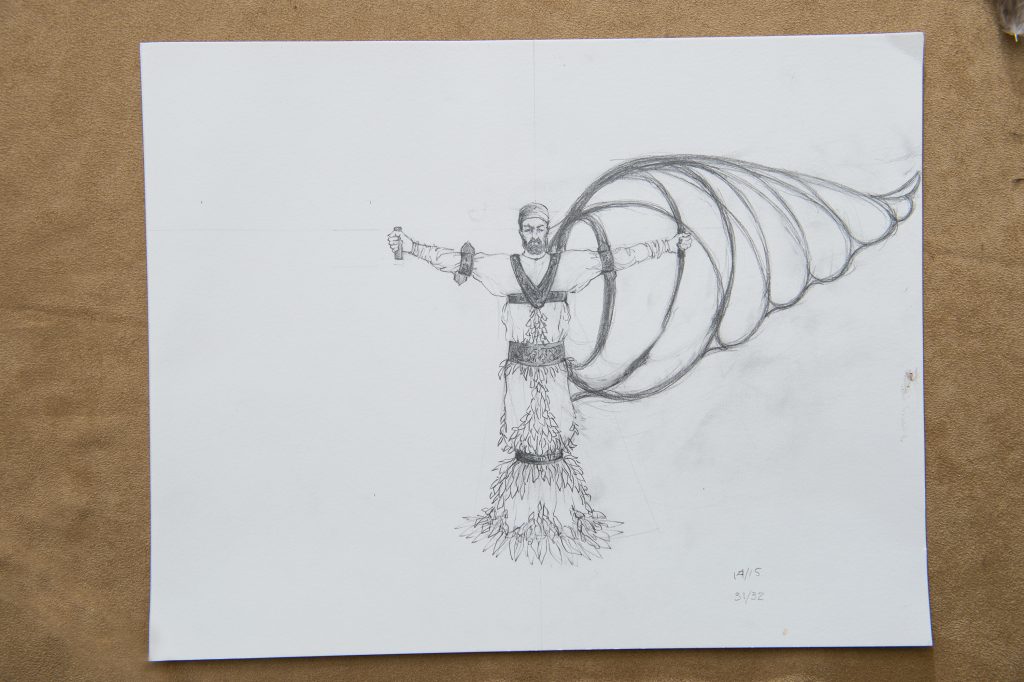

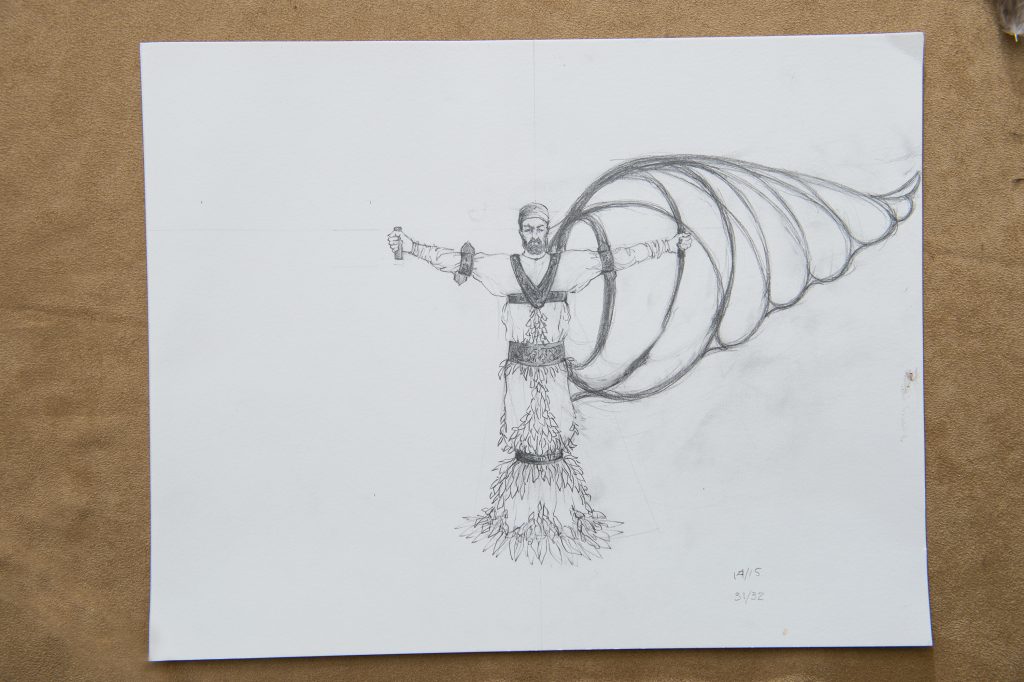

A biomedical engineering student adapted Jan Chamber’s imaginative rendering of Abbas ibn Firnas’ wings into a model that could be printed on a 3-D printer. The scale model was then tested in UNC’s Fluids Lab for its aerodynamic properties. (photo by Steve Exum)

The team received a College of Arts & Sciences Interdisciplinary Collaboration Grant for the project, dubbed “A Medieval ‘First in Flight.’”

Rediscovered manuscript sheds light

There is no known visual representation of Ibn Firnas’ wings. Others have tried to imagine the device, designing utilitarian gliders. Anderson and Chambers wanted to capture the richness of the art and the sophistication of the science of medieval Cordoba, the capital of Islamic Iberia.

Their chief source of inspiration was the earliest historical account of Ibn Firnas’ flight, contained in an 11th-century manuscript that was discovered in the 1930s, lost for several decades and rediscovered in the 1990s.

“This manuscript has yet to be incorporated into scholarship on aviation history,” said Anderson. She worked with other experts to create a new English translation.

From it, she and Chambers gleaned key details, such as the device had two distinct wings capable of a controlled, sustained glide. They didn’t flap. Ibn Firnas’ garment was made of feathers fastened to silk. Witnesses were frightened by the spectacle.

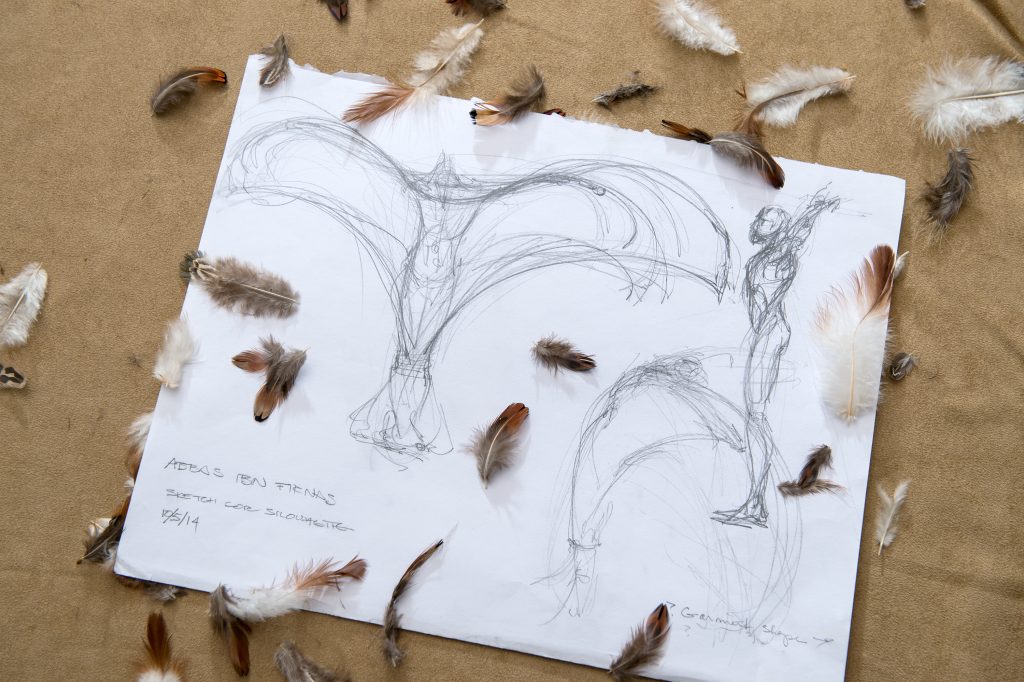

With this information, Chambers set to work. She studied 9th- and 10th-century Islamic artifacts. She watched vultures and eagles — birds mentioned in the Arabic account — glide and soar.

“Glaire and I talked about the lifestyle of the period. This man was an artist as well as a scientist,” Chambers said. “He was capable of crafting these mechanisms. He wouldn’t have settled for something functional. He had a flair for the dramatic.”

She began sketching.

Testing the wings

Costume designer Jan Chambers studied 9th- and 10th-century Islamic artifacts. She watched vultures and eagles — birds mentioned in the Arabic account — glide and soar in creating her sketches. (photo by Steve Exum)

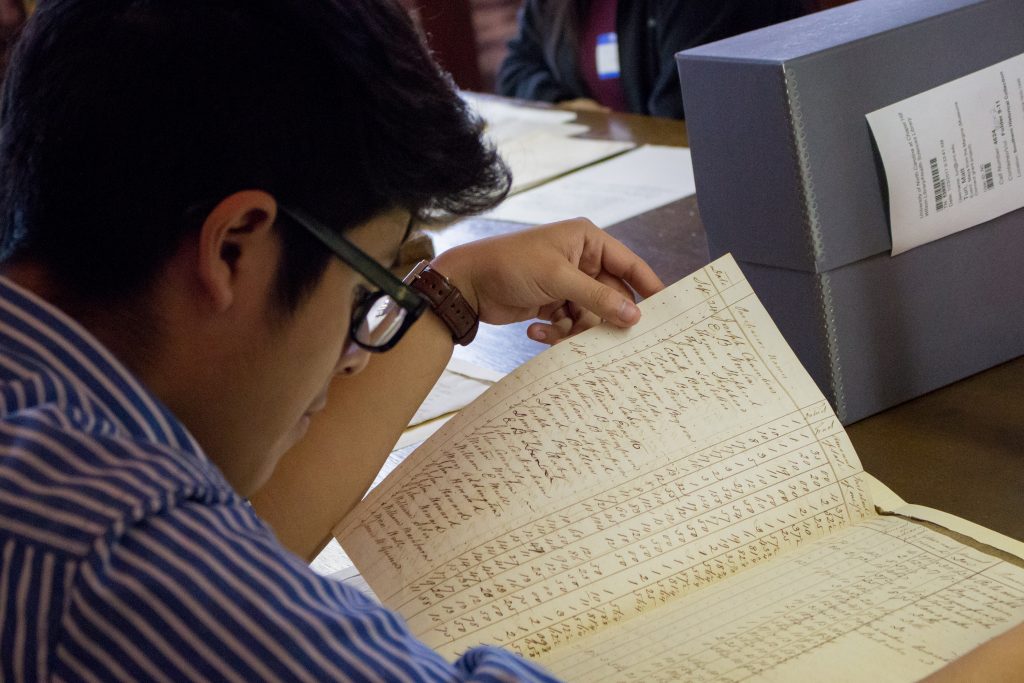

Enter the scientists. After sketching, Chambers used computer software to create 2-D renderings. From them, Kevin Simpson, a biomedical engineering student, designed a digital model that could be created using a 3-D printer.

Miller oversaw the CAP/REU students who worked on the aerodynamic testing. Kimbell helped with using the computational software the students used to guide airways.

The prototype was necessarily small: The wings, attached to a little mannequin, spanned less than 16 inches so that the device could fit into the water tunnel in the fluids lab for testing. (Yes, the wings’ gliding ability was tested in a water tunnel, not a wind tunnel. As Miller explained, air and water flow around objects similarly if scaled appropriately; it’s simply easier to measure velocity in water.)

Meanwhile, Jesse Hall ’15, who worked with Chambers and Anderson, stitched a flying garment for the figure. Claire Drysdale, a junior majoring in studio art and biology, created an interactive timeline for the website that documented the project. “It was my introduction to how technology could be used in art history,” she said.

Anderson is working on a book about Ibn Firnas and the Cordoban court of which he was part. She would love to create a life-size (16-foot wingspan) model of Chambers’ design, estimating that it would cost about $10,000.

As she notes in her project report: “Our collaboration explores how the spheres of art and science have creatively intersected in the past and offers an example of how the visual arts and STEM sciences can fruitfully intersect in the present.”

Learn more about the project at medievalflight.web.unc.edu.

By Geneva Collins

Enjoy a behind-the-scenes look at the photo shoot for the “Synergy Unleashed” feature package!

Read more stories about interdisciplinary mashups:

Helping students explore being Maya

“Spork Lab” tackles password security

Creating a buzz about health humanities

High-tech fluids lab attracts waves of research partners

sciences, Synergy Unleashed symbolizes the power of interdisciplinary work and our commitment to breaking down the silos that hamper collaborative partnerships. After all, “arts” and “sciences” are artificial constructs; the lines between them have always been blurred.

sciences, Synergy Unleashed symbolizes the power of interdisciplinary work and our commitment to breaking down the silos that hamper collaborative partnerships. After all, “arts” and “sciences” are artificial constructs; the lines between them have always been blurred.

“HHIVE is devoted to the centrality of the human story and human expression and to living a meaningful, dignified and productive life,” said Thrailkill, co-director of the lab and of the

“HHIVE is devoted to the centrality of the human story and human expression and to living a meaningful, dignified and productive life,” said Thrailkill, co-director of the lab and of the