Fast, Easy and In Cash: Artisan Hardship and Hope in the Global Economy (University of Chicago Press) by Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld, UNC professor and chair of anthropology, and Jason Antrosio. “Artisan” has become a buzzword in the developed world, used for items like cheese, wine and baskets, as corporations succeed at branding their cheap, mass-produced products with the popular appeal of small-batch, handmade goods. The unforgiving realities of the artisan economy, however, never left the global south, and anthropologists have worried over the fate of resilient craftspeople. Yet artisans are proving to be surprisingly vital players in contemporary capitalism.

Fast, Easy and In Cash: Artisan Hardship and Hope in the Global Economy (University of Chicago Press) by Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld, UNC professor and chair of anthropology, and Jason Antrosio. “Artisan” has become a buzzword in the developed world, used for items like cheese, wine and baskets, as corporations succeed at branding their cheap, mass-produced products with the popular appeal of small-batch, handmade goods. The unforgiving realities of the artisan economy, however, never left the global south, and anthropologists have worried over the fate of resilient craftspeople. Yet artisans are proving to be surprisingly vital players in contemporary capitalism.

Antiracism in Cuba: The Unfinished Revolution (UNC Press) by Devyn Spence Benson (B.A. international studies and Spanish ’01, M.A. history ’04, Ph.D. history ’09). Analyzing the ideology and rhetoric around race in Cuba and south Florida during the early years of the Cuban revolution, Benson argues that ideas, stereotypes and discriminatory practices relating to racial difference persisted despite major efforts by the Cuban state to generate social equality. Drawing on Cuban and U.S. archival materials and face-to-face interviews, Benson examines 1960s government programs and campaigns against discrimination, showing how such programs frequently negated their efforts by reproducing racist images and idioms.

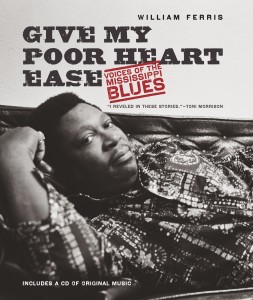

Give My Poor Heart Ease: Voices of the Mississippi Blues (UNC Press, new in paperback) by William Ferris, Joel R. Williamson Eminent Professor of History and senior associate director, Center for the Study of the American South. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, folklorist Ferris toured his home state of Mississippi, documenting the voices of African-Americans as they spoke about and performed the diverse musical traditions that form the authentic roots of the blues. Give My Poor Heart Ease features a searing selection of rich voices from this invaluable documentary record. Illustrated with Ferris’s photographs of the musicians and their communities and including a CD of original music, the book features more than 20 interviews about black life and blues music in the heart of the American South.

Give My Poor Heart Ease: Voices of the Mississippi Blues (UNC Press, new in paperback) by William Ferris, Joel R. Williamson Eminent Professor of History and senior associate director, Center for the Study of the American South. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, folklorist Ferris toured his home state of Mississippi, documenting the voices of African-Americans as they spoke about and performed the diverse musical traditions that form the authentic roots of the blues. Give My Poor Heart Ease features a searing selection of rich voices from this invaluable documentary record. Illustrated with Ferris’s photographs of the musicians and their communities and including a CD of original music, the book features more than 20 interviews about black life and blues music in the heart of the American South.

NC 12: Gateway to the Outer Banks (UNC Press) by Dawson Carr (B.S. mathematics ’58, M.A. ’65 and Ph.D. ’76 education). Connecting communities from Corolla in the north to Ocracoke Island in the south, scenic North Carolina Highway 12 binds together the fragile barrier islands that make up the Outer Banks. Throughout its lifetime, however, NC 12 has faced many challenges — from recurring storms and shifting sands to legal and political disputes — that have threatened this remarkable highway’s very existence. Throughout the book, Carr captures the personal stories of those who have loved and lived on the Outer Banks.

NC 12: Gateway to the Outer Banks (UNC Press) by Dawson Carr (B.S. mathematics ’58, M.A. ’65 and Ph.D. ’76 education). Connecting communities from Corolla in the north to Ocracoke Island in the south, scenic North Carolina Highway 12 binds together the fragile barrier islands that make up the Outer Banks. Throughout its lifetime, however, NC 12 has faced many challenges — from recurring storms and shifting sands to legal and political disputes — that have threatened this remarkable highway’s very existence. Throughout the book, Carr captures the personal stories of those who have loved and lived on the Outer Banks.

Ticket: A Guidebook for the Table by Kimberly Kyser (B.A. art history ’68), a Chapel Hill artist, designer and writer. For those who have wondered what relevance table manners could have for them, consider the story told by Greg Fitch about the time when renowned University of North Carolina basketball coach Dean Smith called up his mother, Jenny Fitch — the creator and inspiration of The Fearrington House Inn and Restaurant — to request a private tutorial in table manners for his team. Fitch welcomed the young athletes who learned, as Kyser points out, that social skills can improve grades, careers and lives.

From Brown to Meredith: The Long Struggles for School Desegregation in Louisville, Kentucky, 1954-2007 (UNC Press) by Tracy E. K’Meyer (M.A. ’89 and Ph.D. ’93 history). K’Meyer is a professor of history and co-director of the Oral History Center at the University of Louisville. When the Supreme Court overturned Louisville’s local desegregation plan in 2007, the people of Jefferson County, Kentucky, faced the question of whether and how to maintain racial diversity in their schools. Using oral history narratives, newspaper accounts and other documents, K’Meyer exposes the disappointments of desegregation, draws attention to those who struggled for over five decades to bring about equality and diversity, and highlights the many benefits of school integration.

From Brown to Meredith: The Long Struggles for School Desegregation in Louisville, Kentucky, 1954-2007 (UNC Press) by Tracy E. K’Meyer (M.A. ’89 and Ph.D. ’93 history). K’Meyer is a professor of history and co-director of the Oral History Center at the University of Louisville. When the Supreme Court overturned Louisville’s local desegregation plan in 2007, the people of Jefferson County, Kentucky, faced the question of whether and how to maintain racial diversity in their schools. Using oral history narratives, newspaper accounts and other documents, K’Meyer exposes the disappointments of desegregation, draws attention to those who struggled for over five decades to bring about equality and diversity, and highlights the many benefits of school integration.

Understanding Gish Jen (The University of South Carolina Press) by Jennifer Ho, associate professor of English and comparative literature. A second-generation Chinese American, Gish Jen is widely recognized as an important American literary voice, at once accessible, philosophical and thought-provoking. Ho traces the evolution of Jen’s career, her themes and the development of her narrative voice. In the process, she shows why Jen’s observations about life in the United States, though revealed through the perspectives of her Asian American and Asian immigrant characters, resonate with a variety of audiences.

Building the British Atlantic World: Spaces, Places and Material Culture, 1600-1850 (UNC Press) edited by Bernard L. Herman, George B. Tindall Distinguished Professor of Southern Studies and Folklore and chair of American studies, and Daniel Maudlin, professor of early modern history at the University of Plymouth. Spanning the North Atlantic rim from Canada to Scotland, and from the Caribbean to the coast of West Africa, the British Atlantic world is deeply interconnected across its regions. In this groundbreaking study, 13 leading scholars explore the idea of “transatlanticism” — or a shared “Atlantic world” experience — through the lens of architecture, built spaces and landscapes in the British Atlantic from the 17th century through the mid-19th century.

Barbecue: A Savor the South cookbook (UNC Press) by John Shelton Reed, professor emeritus of sociology. Barbecue celebrates a southern culinary tradition forged in coals and smoke. Since colonial times, southerners have held barbecues to mark homecomings, reunions and political campaigns; today barbecue signifies celebration as much as ever. In a lively and amusing style, Reed traces the history of southern barbecue from its roots in the 16th century Caribbean. He also provides 51 recipes for many classic varieties of barbecue and for the side dishes, breads and desserts that usually go with it.

Barbecue: A Savor the South cookbook (UNC Press) by John Shelton Reed, professor emeritus of sociology. Barbecue celebrates a southern culinary tradition forged in coals and smoke. Since colonial times, southerners have held barbecues to mark homecomings, reunions and political campaigns; today barbecue signifies celebration as much as ever. In a lively and amusing style, Reed traces the history of southern barbecue from its roots in the 16th century Caribbean. He also provides 51 recipes for many classic varieties of barbecue and for the side dishes, breads and desserts that usually go with it.

Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (Harper Collins) by Bart D. Ehrman, James A. Gray Distinguished Professor of religious studies. The bestselling author of Misquoting Jesus examines oral tradition and its role in shaping the stories about Jesus we encounter in the New Testament. Throughout much of human history, our most important stories were passed down orally — including the stories about Jesus before they became written down in the Gospels. In this deeply researched work, Erhman investigates the role oral history has played in the New Testament — how the telling of these stories not only spread Jesus’ message but helped shape it.

Irrepressible: The Jazz Age Life of Henrietta Bingham (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) by Emily Bingham (MA ’91 Ph.D. ’98 history). Raised like a princess in one of the most powerful families in the American South, Henrietta Bingham was offered the helm of a publishing empire. Instead, she ripped through the Jazz Age like an F. Scott Fitzgerald character: intoxicating and intoxicated, selfish and shameless, seductive and brilliant, endearing and often terribly troubled. Henrietta rode the cultural cusp as a muse to the Bloomsbury Group, the daughter of the ambassador to the United Kingdom during the rise of Nazism, the seductress of royalty and athletic champions, and a pre-Stonewall figure who never buckled to convention. Historian and biographer Emily Bingham says the secret of who her great-aunt was, and just why her story was concealed for so long, led her to write this biography.

Irrepressible: The Jazz Age Life of Henrietta Bingham (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) by Emily Bingham (MA ’91 Ph.D. ’98 history). Raised like a princess in one of the most powerful families in the American South, Henrietta Bingham was offered the helm of a publishing empire. Instead, she ripped through the Jazz Age like an F. Scott Fitzgerald character: intoxicating and intoxicated, selfish and shameless, seductive and brilliant, endearing and often terribly troubled. Henrietta rode the cultural cusp as a muse to the Bloomsbury Group, the daughter of the ambassador to the United Kingdom during the rise of Nazism, the seductress of royalty and athletic champions, and a pre-Stonewall figure who never buckled to convention. Historian and biographer Emily Bingham says the secret of who her great-aunt was, and just why her story was concealed for so long, led her to write this biography.

Free Men: (HarperCollins) by Katy Simpson Smith (Ph.D. history). From the author of the highly acclaimed The Story of Land and Sea comes a captivating novel, set in the late eighteenth-century American South, that follows a singular group of companions — an escaped slave, a white orphan, and a Creek Indian — who are being tracked down for murder. The Washington Post wrote: “With this collage of experiences twisted together and soaked in blood, Smith cuts to the bone of our national character. Then, as now, for all its violence and desperation, it’s noble and inspiring, too.”

Read an excerpt from Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett by Bernard L. Herman.

Q: How is creativity important to your work as a scientist?

Q: How is creativity important to your work as a scientist?

Q: How is creativity important to your work as professor?

Q: How is creativity important to your work as professor?

Fast, Easy and In Cash: Artisan Hardship and Hope in the Global Economy

Fast, Easy and In Cash: Artisan Hardship and Hope in the Global Economy

Give My Poor Heart Ease: Voices of the Mississippi Blues

Give My Poor Heart Ease: Voices of the Mississippi Blues NC 12: Gateway to the Outer Banks

NC 12: Gateway to the Outer Banks From Brown to Meredith: The Long Struggles for School Desegregation in Louisville, Kentucky, 1954-2007

From Brown to Meredith: The Long Struggles for School Desegregation in Louisville, Kentucky, 1954-2007

Barbecue: A Savor the South cookbook

Barbecue: A Savor the South cookbook

Irrepressible: The Jazz Age Life of Henrietta Bingham

Irrepressible: The Jazz Age Life of Henrietta Bingham