Ronald Lockett, hands thrust deep into the pockets of his dark slacks, studies the artwork he’s tilted against the corner of his garage studio in Bessemer, Ala. His composition, roughly four feet square, consists entirely of found materials: rusted roofing and siding tin nailed to a weathered board backing. A small vertical rectangle of metal painted white brightens and anchors the hand-cut oxidized metal panels, some crumpled, others bearing traces of worn and abraded paint. Always thoughtful in his responses, he speaks away from the camera even as he assesses the work he has made. “This is called Oklahoma,” he begins, “this is the idea I came up with to express my idea about the Oklahoma bombing. It’s sort of abstract, with cut out different shapes and stuff, with wire and old tin, and barbed wire.” He remembers, “I wanted to come up with the best idea I could without offending any of those people that had families that got killed in this federal building.”

Ronald Lockett was born in 1965 and lived the entirety of his life in the Pipe Shop neighborhood of the old manufacturing city of Bessemer, Ala., southwest of Birmingham. His home on Fifteenth Street stood in a row of modest working class bungalows owned and occupied by his extended family, including two of the most influential people in his artistic life — his great aunt Sarah Dial Lockett (whom he memorialized in Sara Lockett’s Roses (1997)) and his cousin, the much revered Thornton Dial, who passed away in 2016. His cousin Richard Dial remembered Lockett, “Ronald was one of the most easy-going fellows that you would ever run across. … He was just a calm fellow and that was his life. He just wanted to live and try to get along with everybody … and he got along with everybody.” His art came to the attention of Thornton Dial’s friend and patron William (Bill) Arnett in the late 1980s. His early efforts developed in the context of his relationship with Dial, whose studio stood in the “junk house” just down the street. Lockett worked as an artist until his death from HIV/AIDS in 1998. His total known production numbers roughly between 350 and 400 works. In the end, however, much about Ronald Lockett’s life and art remains a mystery.

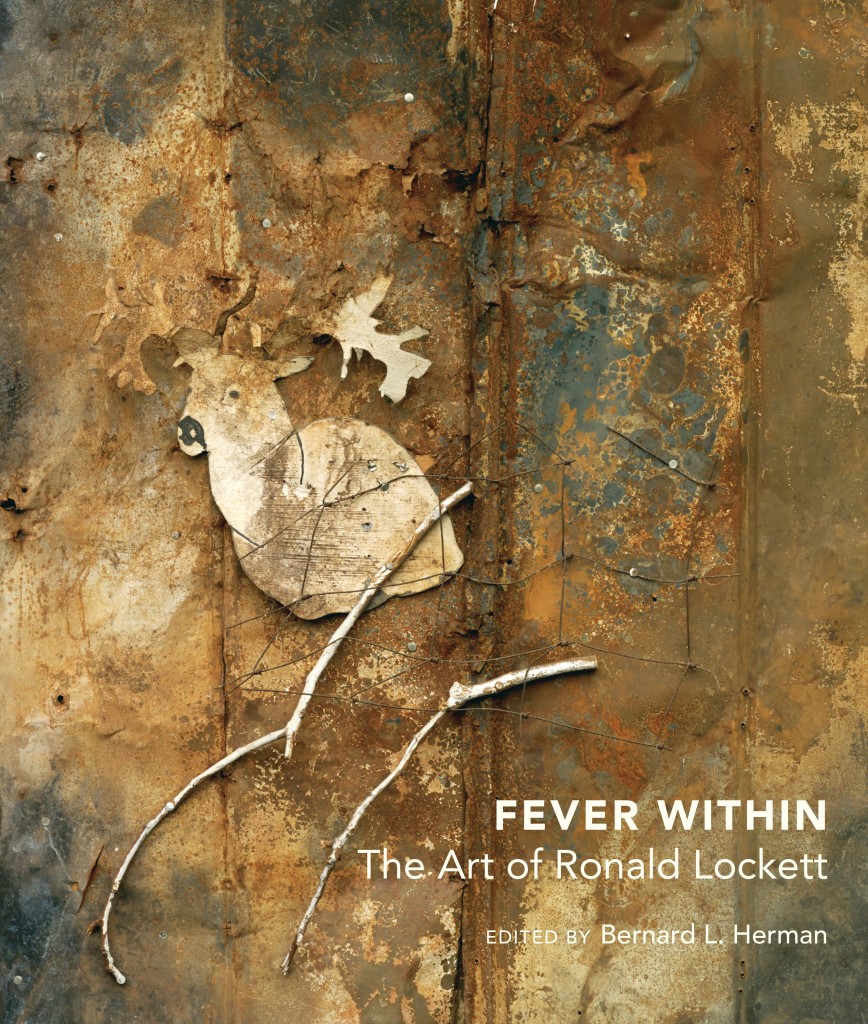

Several series of works that Lockett undertook from the late 1980s through 1997 provide a richer biographical understanding of his artistic growth, his influences and the continuing concerns that ran through all of his work. Although Lockett devoted the major share of his energies to more serious themes reflected in series such as Oklahoma, and a late collection of works on women, in particular Princess Diana and Sarah Dial Lockett, he could at times be playful, as seen in his sculptures of horses and an elephant. At the same time he developed these continuing themes, Lockett produced a variety of additional works through which he examined parallel issues and perfected his techniques through experimentation and practice.

The Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill has organized a traveling exhibition that is the first solo show of Lockett’s work, with shows at the American Folk Art Museum in New York (June 21 -Sept. 18, 2016), High Museum of Art in Atlanta (Oct. 9, 2016 -Jan. 8, 2017) and the Ackland (Jan. 27-April 9, 2017).

Excerpt from Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett, edited by Bernard L. Herman (UNC Press, June 2016). Herman is George B. Tindall Distinguished Professor of Southern Studies and chair of the department of American studies.