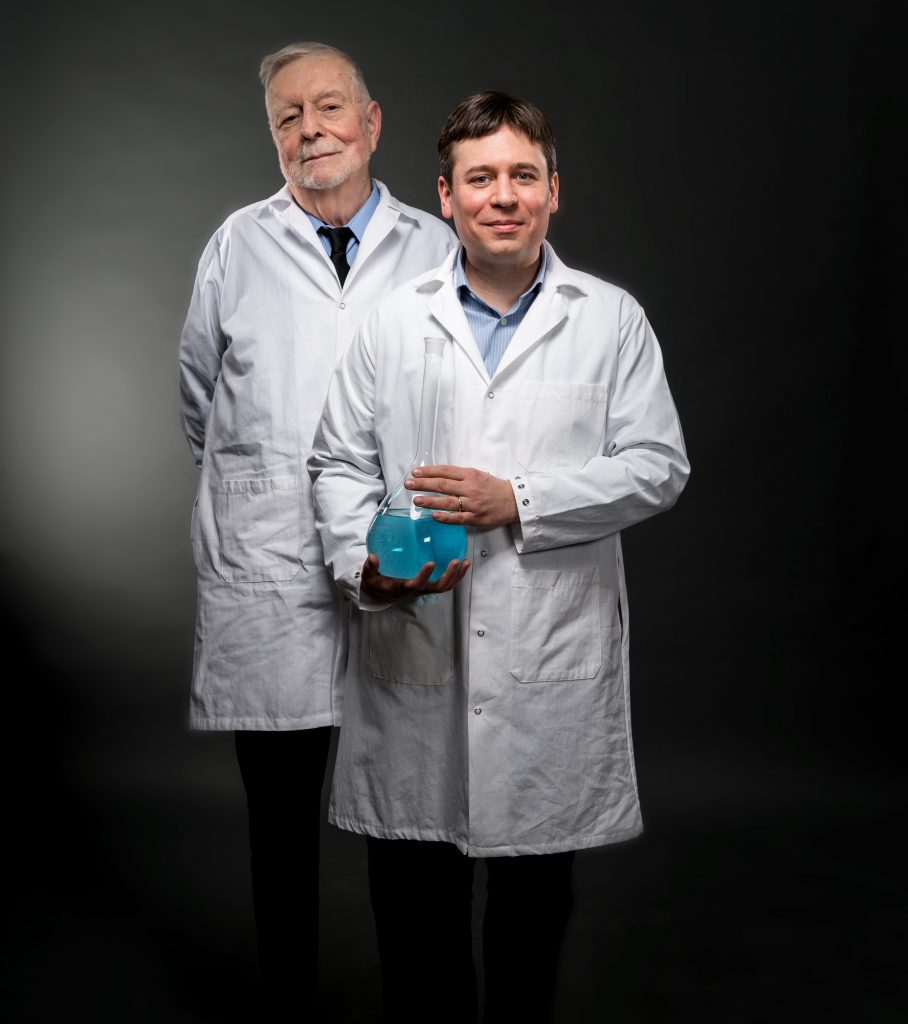

Bo Li is one of Carolina chemistry’s rising young stars. Behind her is Royce Murray, who has been with the department for nearly six decades and for whom Murray Hall is named. (photo by Steve Exum)

In the four years since she has come to UNC-Chapel Hill, Bo Li has won recognition after recognition for her work in understanding how bacterial small molecules may help defend the body against infectious diseases, with an eye toward developing the next generation of antibiotics.

Top awards include some of the most prestigious honors given to young scientists: a New Innovator Award from the National Institutes of Health, a National Science Foundation CAREER Award, a Packard Fellowship for Science and Engineering, and a Rita Allen Foundation Scholars Award for biomedical research.

Li, an assistant professor of chemistry, was attracted to the chemistry department’s collegial atmosphere and the opportunity to collaborate with infectious disease researchers across campus, including pharmacy, medicine and biology.

In April, Carolina chemistry will celebrate its 200th birthday. A key secret to reaching this venerable milestone and achieving an international reputation has been to invest in generations of promising young scientists like Li and to provide them with the tools they need to thrive. Today, young scholars continue to work alongside foundational members of the department — people like Royce Murray, who has been on the faculty for 58 years.

Chemistry department chair Jeffrey Johnson teaches graduate students in “Synthetic Organic Chemistry.” As the department celebrates its 200th birthday, he says “this is a pivotal time for Carolina chemistry.” (photo by Steve Exum)

Investing in rising stars has been a hallmark of the department since the William F. Little era. Little came to Carolina as a chemistry instructor in 1956 and nine years later, at age 35, became chair. Regarded as the heart, soul and energizing force of the chemistry department, he created a congenial environment in which excellence was expected and success was widely celebrated.

Rather than hiring more senior faculty, as was done elsewhere to raise a department’s profile, he hired promising young scholars, invested significant resources in furthering their research and aided them in getting tenure, trusting that many would remain at Carolina and continue to contribute.

In five years, Little nearly doubled the number of faculty members — up to 30 — and elevated the department’s stature. He understood that bringing in new faculty required expanding lab space well beyond Venable Hall, chemistry’s home since 1925, so he aggressively sought funding to build Kenan Labs, which opened in 1971.

“With improved lab space, you can do a better job recruiting the best and brightest faculty and students, so getting Kenan built was huge,” said renowned inorganic chemist Joe Templeton, Francis Preston Venable Professor of Chemistry, who has been at Carolina since 1976.

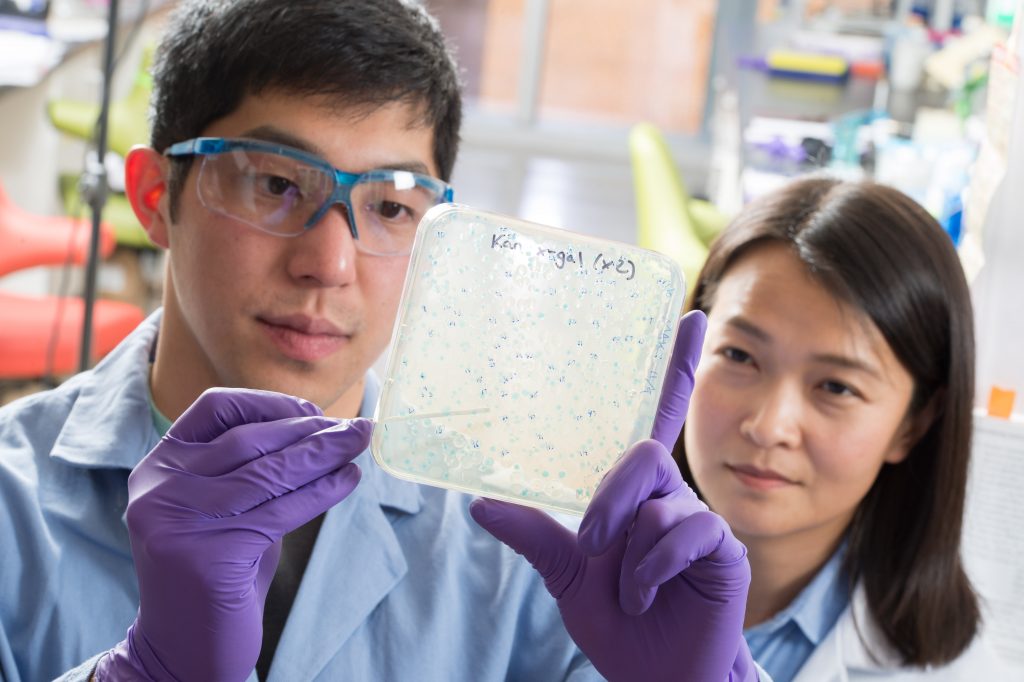

Chemistry graduate student Andrew Chan (with Bo Li) uses a blue-white screen to isolate mutant bacteria deficient in making an antibiotic. This method helps determine the bacterial genes involved in the synthesis of the antibiotic, so these genes can be used to guide the discovery of new antibiotics. (photo by Steve Exum)

Likewise, the Carolina Physical Science Complex, which broke ground in 2004, has had a significant impact on recruiting the current generation of scientists. “That kind of huge investment pays off for decades, and Bill really started that thinking long ago,” Templeton said.

Little also was a driving force behind the creation of Research Triangle Park and Research Triangle Institute.

His first love, though, was the chemistry department, then-Chancellor Holden Thorp said when Little died in 2009.

“He created a culture where the coins of the realm were wisdom and encouragement. He was a giant,” said Thorp, who studied under Little in the 1980s and became chemistry chair in 2005. (Thorp went on to serve as dean of the College of Arts & Sciences, then Carolina’s chancellor; he is now provost at Washington University in St. Louis.)

Giants of chemistry

Denison Olmsted was the first professor hired by the chemistry department in 1818. (photo courtesy of N.C. Collection, University Libraries)

UNC’s chemistry department dates its origins back to the hiring of its first professor, Denison Olmsted, who taught chemistry and mineralogy, arriving in Chapel Hill in 1818 and staying for eight years.

As the chemistry department grew, it attracted the man who would become known as the founding father of Carolina chemists, Francis P. Venable, in 1880.

Almost immediately, Venable set the department on a quest for knowledge. He was the first faculty member to hold an earned Ph.D. (instead of an honorary doctorate), and in 1893 was named to the first endowed chair at UNC, the Mary Ann Smith Professorship, to “teach both the science of chemistry and its experimental application to the useful arts.”

In 1900, Venable moved from the chemistry department in Person Hall to South Building, where he served as UNC’s president for 14 years. During his tenure, Venable oversaw a significant increase in both students and faculty. He returned to the chemistry department as chair in 1914.

Francis P. Venable, dubbed the “founding father of Carolina chemists,” also served as the University’s president. (photo courtesy of N.C. Collection, University Libraries)

His exams always began with the question, “What is chemistry?” The acceptable answer was: “that branch of sciences which investigates … the synthesis and analysis of matter.”

That definition only scratches the surface of what chemistry involves today, said Maurice Bursey, but the question was a good starting point. Bursey, an award-winning professor emeritus of chemistry, wrote the departmental history Carolina Chemists, published in 1982 to celebrate the centennial of Venable’s arrival at UNC. Another book, seven years later, focused exclusively on Venable.

Venable retired in 1930, but two of his students, John Motley Morehead and William Rand Kenan Jr., would go on to profoundly influence the trajectory of 20th-century American industry — as well as UNC’s way forward.

After completing chemistry courses in 1891, Morehead teamed with a Canadian inventor to seek an inexpensive way to produce pure aluminum. One experiment created a dark, glassy rock — calcium carbide.

When calcium carbide was placed in water, it released acetylene gas, and when the colorless gas was mixed with air, it burned brightly, Venable and Kenan found.

It would take several more years, but the perseverance of Venable, Kenan and Morehead led to the world’s first commercial calcium carbide plant, which later became Union Carbide. Acetylene is still used for welding and metal cutting and as a raw material in the synthesis of many organic chemicals and plastics. (For more on these “Kings of Chemistry,” visit endeavors.unc.edu/kings_of_chemistry.)

Maurice Bursey (left) and James Cahoon. Bursey taught at Carolina for 30 years before retiring in 1996. Cahoon came to UNC in 2011 to further his work on novel semiconductor nanowires and nanomaterials. (photo by Steve Exum)

Emerging prestige

In the second half of the 20th century, the chemistry department grew both in rank and prestige.

When Murray arrived in 1960 (just a few years after Little), the faculty numbered fewer than 15 and all worked from labs in the sprawling ranch-style Venable Hall. There were two National Academy of Sciences (NAS) members in the department, and Murray — an analytical chemist with research interests in electrochemistry, molecular design and sensors — brought that number to five by 1991. Today, the nearly 50 faculty members include seven NAS members.

Murray has amassed just about every major honor in his field, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, plus fellowships in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, as well as being named editor of the preeminent journal in his field, Analytical Chemistry.

University administrators have turned to the Kenan Professor of Chemistry and former department chair to help guide the design of new lab facilities — first Kenan Labs, and later, the physical science complex.

For the latter project, Murray formed a building committee of chairs whose departments would be housed in the new facilities. That group, plus the architect’s belief that a building should adapt to its users’ needs, helped ensure the project’s success, Murray said.

One building bears his name, thanks in large part to one of his former students. Lowry Caudill, who did his senior research in Murray’s lab before graduating in 1979, provided the $5 million gift that funded the naming of Murray Hall.

Caudill, an accomplished analytical chemist and entrepreneur, co-founded Magellan Laboratories in 1991 and served as worldwide president of pharmaceutical development for Cardinal Health when it acquired Magellan. He is a past chair of Carolina’s Board of Trustees and is an adjunct professor of chemistry. The science complex’s new chemistry building is named after Caudill and his wife, Susan.

Ask another Little devotee, Maurice Brookhart, about Carolina chemistry, and the William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Chemistry points to a track record of success.

He described the department as a booming research enterprise that remains strong in the core areas of organic, inorganic, physical and analytical chemistry while expanding in materials science, biological chemistry, catalysis and applied sciences.

“We’re not doing things much differently than other top-20 chemistry departments in terms of the way we’re structured and the way we teach — we’re just really good!” said Brookhart, an award-winning chemist in catalysis and NAS member, who joined the faculty in 1969 and retired three years ago.

The widespread spirit of cooperation continually brings in good young faculty and keeps them here, he added.

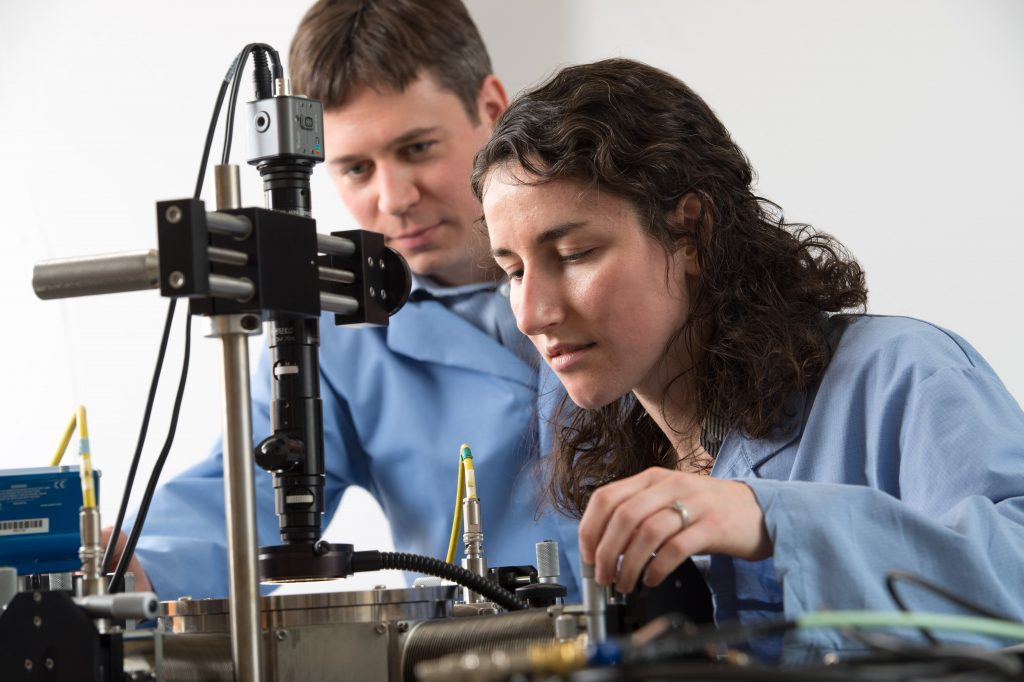

Chemistry graduate student Taylor S. Teitsworth (with James Cahoon, left) uses a cryogenic probe station, which allows her to perform electrical measurements on semiconductor nanowire materials at very low temperatures. (photo by Steve Exum)

Faculty with a collective goal

One of those rising stars is Jillian Dempsey, who came to Carolina in 2012 to establish her vibrant research program in physical inorganic chemistry.

“I was excited to take on this lofty goal of building a lab, knowing I had the support of some really wonderful people,” the assistant professor said. “That’s what distinguishes our department — having faculty with a collective goal, a great department instead of individual faculty who simply want great research programs in their own labs.”

Dempsey and her lab are studying next-generation catalysts for artificial photosynthesis with an eye toward developing renewable, high-energy fuels from inexpensive, abundant reactants. In 2015, she received a Packard Fellowship, and she is also a recipient of an NSF CAREER Award and a Sloan Fellowship.

In recent years, Dempsey has seen an uptick in the number of talented young scientists joining the faculty and, in turn, the department’s response in meeting their unique needs — including meetings geared toward junior faculty or female chemists. In addition, a new Clare Boothe Luce Program led by Dempsey will support fellowships for women in chemistry (see sidebar, page 7).

For associate professor James Cahoon, coming to Carolina in 2011 provided the opportunity to further his work on novel semiconductor nanowires and nanomaterials.

“At the time, this was a relatively new research direction for Carolina chemistry,” said Cahoon.

Semiconductors are used in a range of technologies, from solar cells that convert sunlight into electricity to microprocessors that drive computers. Cahoon’s group uses a multidisciplinary approach involving chemistry, physics, materials science and engineering to advance their research.

Like his prize-winning colleagues, in 2016 Cahoon received an NSF CAREER Award, and last year the University awarded him a Phillip and Ruth Hettleman Prize for Artistic and Scholarly Achievement by Young Faculty. Those honors followed Sloan and Packard fellowships. Cahoon serves as the UNC site director of the Research Triangle Nanotechnology Network.

Joseph DeSimone (right) with his first doctoral student, Valerie Ashby (far left), around 1990. DeSimone is one of Carolina’s most accomplished professors and entrepreneurs. Ashby is now dean of Duke University’s Trinity College of Arts & Sciences. (photo courtesy of N.C. Collection, University Libraries)

Benefiting society

Within a department of exceptional researchers, professor Joseph DeSimone has an unparalleled entrepreneurial track record.

With nearly 200 patents to his name and multiple startups under his belt, DeSimone has been an innovator in fields as diverse as creating environmentally safe processes for high-performance plastics to developing bioabsorbable surgical devices.

DeSimone, Chancellor’s Eminent Professor of Chemistry at UNC, is one of only a handful of people nationwide who have been elected to all three branches of the U.S. national academies — medicine, engineering and sciences — among his many other honors. In 2016, President Barack Obama awarded DeSimone the U.S. National Medal of Technology and Innovation.

“The department has always been highly encouraging of faculty members’ entrepreneurial activities, recognizing that discoveries in the lab not only advance our discipline, but also have the potential to impact society,” said DeSimone, who has also been a champion of diversity in STEM.

His most recent work has been in advanced manufacturing, where DeSimone’s technology — known as continuous liquid interface production, or CLIP — has reimagined 3-D printing. His Silicon Valley company, Carbon (co-founded with UNC professor Ed Samulski and Alex Ermoshkin, formerly of DeSimone’s UNC lab) uses CLIP technology to fabricate parts up to 1,000 times faster than other 3-D printers on the market. The materials produced have optimal properties for use in diverse industries — from athletic footwear to consumer electronics to medical devices. An Adidas running shoe called Futurecraft 4D was manufactured using Carbon technology and went on sale in January.

The award-winning polymer scientist has been connected to Carolina for nearly three decades.

“My research effort over time has grown to involve a wide range of disciplines,” he said, “so having a home in one of the best chemistry departments in the country, joined with the ability to collaborate with world-renowned experts in immunology, biology, pharmacology and other areas has been a huge motivator in making Carolina my home institution for most of my career.”

DeSimone’s first Ph.D. student, Valerie Sheares Ashby, is just one example of Carolina chemistry alumni who have gone on to do great things. Ashby received her undergraduate and doctoral degrees in chemistry in 1988 and 1994, respectively. She returned to UNC to teach in 2003 and became the first female and first African-American chair of the chemistry department in 2012. In 2015, she was named dean of Trinity College of Arts & Sciences at Duke University.

When the department of chemistry celebrates its 200th birthday during the weekend of April 20-21, DeSimone and other chemistry legends will celebrate the past and look to the future.

That future currently rests in the hands of department chair Jeffrey Johnson, the A. Ronald Gallant Distinguished Professor of Chemistry, who came to UNC in 2001.

“This is a pivotal time for Carolina chemistry. Going forward, we want to capitalize on Carolina’s strengths in energy, materials science and the interface with biomedical fields,” said Johnson. “We also want to increase our touch in interdisciplinary, highly collaborative projects that benefit society.”

In any area, though, it’s the people who make a difference, he added. “Since the beginning, people have always been the calling card of our department, and their collegiality and shared sense of purpose make Carolina chemistry unique.”

Read a sidebar on a new grant to support female chemists and check out a timeline of Carolina Chemistry.

Watch a video about 200 years of Carolina Chemistry.

See the April 20-21 bicentennial celebration schedule.

Learn about successful chemistry startups Carbon and Ribometrix.

By Patty Courtright (B.A. ’75, M.A. ’83)