What was once the region’s largest textile mill under one roof is now the subject of the largest digital humanities project ever undertaken by the University.

Digital Loray came together through a near-perfect alignment of business, education and technology. Loray Redevelopment LLC partner Billy Hughes wanted to include the 113-year history of Gastonia’s Loray Mill in a $39 million transformation of the structure into modern apartments, offices and stores. The developer set aside 1,100 square feet at entry level for a history center, as a resident amenity and visitor attraction. Carolina alumnus Rick Kessell contributed the funds for the center in honor of his father, Alfred C. Kessell.

Robert Allen, director of Carolina’s Digital Innovation Lab (DIL) in the College of Arts and Sciences, seized the opportunity to show just what his growing digital humanities lab could do. The Loray Mill project was perfect for the DIL, which focuses on bringing together the humanities and digital technology, promoting community involvement, assuring public access and building systems that can be easily adapted to other projects.

Bobby Allen (left) said: “This is a great example of the impact the University can have in local communities across the state. We are uniquely capable and positioned to do this.”

Digital Loray is not only DIL’s biggest project so far, it’s also the most ambitious public digital humanities project the University has ever undertaken, according to Allen, James Logan Godfrey Distinguished Professor of American Studies. The project has resulted in a rich digital archive and interpretive tools reflecting the history of the mill, the mill village and people and events associated with the mill over more than 110 years.

Libraries and museums in small cities like Gastonia, 25 miles west of Charlotte, do not have the resources to create something like this on their own. The project required a top public research university with a commitment to engaged scholarship, said Allen, who grew up in Gastonia and has family roots in the Loray/Firestone community.

“This is a great example of the impact the University can have in local communities across the state. We are uniquely capable and positioned to do this,” he said.

The Place

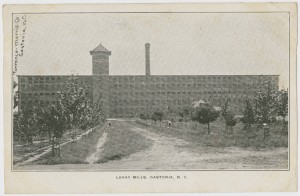

Loray Mill is massive. A Romanesque Revival tower looms over five stories of red brick framing banks of tall windows. The interior is more than a half-million square feet.

Loray Mill is massive. A Romanesque Revival tower looms over five stories of red brick framing banks of tall windows. The interior is more than a half-million square feet.

Founded by two local families (Love and Gray) the Loray Mill dominated Gaston County’s economy as much as it did the landscape. Like most mills of the era, it was its own community, equipped to make its own bricks and shoe its own horses. More than 1,000 employees lived in the 30-block, company-owned village adjacent to the mill.

In 1935, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company bought the mill to produce tire fabric. At the height of production, 2,500 people worked in the mill. Firestone began to sell the mill houses to their tenants in the 1940s. In 1993, Firestone closed Loray and moved its operations to King’s Mountain.

But the mill was preserved. While other vacant textile mills were reduced to rubble, Loray Mill survived because Firestone donated the property to Preservation North Carolina in 1998. The mill and about 350 surrounding mill houses now comprise a National Register of Historic Places district.

The Data

Karen Sieber views an archive slide.

Luckily for the project, the mill has been well documented, although not always positively. In 1908, famed photographer Lewis Hine came to Loray to document child labor practices. Allen ran across his portraits of grubby working kids, several of whom lived on the same street as his grandfather, in the Library of Congress. The mill is also famous for the violent Loray Mill strike of 1929, when a policeman and a labor activist were both killed in the turmoil of an attempt to organize a union.

Many publications of the day ran stories and images about the strike and related murder trial, some now digitized. The North Carolina Digital Heritage Center (housed in Wilson Library) also digitized the whole 1952–1993 run of Firestone News, the company newspaper. Census forms provide a data snapshot every 10 years. Gastonia residents and former employees, the Gaston County Museum of Art and History and the Gaston County Library also allowed the team to digitize photos, clippings and other artifacts.

The ever-expanding digital archive includes more than 2,000 images, scanned and documented as much as possible. The items have color-coded frames and can be viewed by topic, location or source. Census data combined with fire insurance maps inform an interactive map of the mill village in the 1920s. Click on a house to see its address and photo. Then click on the dot representing a resident of the house and discover the person’s name, address, race, occupation and relationship to the householder. Students in Allen’s 2015 spring seminar traced the journey of African-American families from farm work in South Carolina to mill work at Loray.

The Historian

Spacious hallways and log beams are part of the renovated mill project.

The public face of Digital Loray is Julie Davis, who joined the team in September 2014 as a Carolina Digital Humanities Initiative Postdoctoral Fellow, supported through a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Davis is project director and historian-in-residence at the mill. (The developer is subsidizing one of the new loft apartments there for her use.) She is working with local organizations to create innovative public programming that makes full use of Digital Loray.

One of her first jobs was to incorporate history into the March 26 grand re-opening of the mill, attended by more than 400 business and civic leaders, including Gov. Pat McCrory. Davis and her team worked with community partners to produce content for six interactive history stations placed throughout the event space.

The Students

Carolina students have done much of the research needed to populate Digital Loray, not only online but also by going to Gastonia to meet with community members, hear their stories and dig through boxes of memorabilia.

The interactive map of the mill village in the 1920s began as an independent study project by Karen Sieber, who is combining a major in American Studies with a self-designed concentration in urban history. From a six-block visualization, the map expanded to more than 100,000 data points on over 2,000 residents of the mill village in 1920. Now Sieber is preparing to collect data for 1930, to track demographic changes over time. The archive also includes seven household spotlights prepared by Sieber and five American studies graduate students that give more details about the families and their history.

An old photo of the mill.

Elijah Gaddis, a doctoral student in American studies, has worked on the project for the past 18 months. He built and imaged the database for the digital archive and created the online displays of the archive and timelines of the mill’s history.

“Doing this kind of work on a more institutional level is really important and is something that I want to see UNC doing more of, both as a student and as a North Carolinian,” said Gaddis, a native of Cabarrus County.

Lindsay Ogles is a recent graduate of the School of Information and Library Science who also worked with the North Carolina Collection. For the Loray Mill project, she is designing a 3-D map of the mill village, complete with virtual peeks inside based on floor plans.

The Community

The Digital Loray team is adamant that they couldn’t have done their work without the help of the community. Specifically, Passmore and Lucy Penegar, vice chair of the Gaston County Historic Preservation Commission, both contributed thousands of photos and artifacts to the project and led mill tours.

In exchange, Gastonia residents get what Sieber calls “an anchor” for their memories, a digital anchor they couldn’t have made by themselves. “There is not a person in town without some sort of connection to the mill, even if they themselves never worked there,” she said. “People crave a place where they feel their stories, and often the stories of the generations that came before them, are heard.”

Eventually, the mill and its history center could become a destination for tourists, history lovers, researchers and genealogists.

Meanwhile, the team still needs the help of the community for this ongoing project. They encourage anyone with stories to tell and memories to share about the mill or the village to contact them through the Digital Loray website or by emailing loraydigital@unc.edu.

The Donor

The Army Navy Efficiency Flag presented to Firestone mill. From left, former employee Bill Passmore, Ph.D. student Elijah Gaddis and Digital Innovation Lab director Bobby Allen.

Many different organizations have provided funding for the project, but the gift that laid the groundwork for Digital Loray dates back to 2008. That’s when Allen became the first recipient of the C. Felix Harvey Award To Advance Institutional Priorities and received $75,000 to fund “Main Street, Carolina.”

Given annually, the Harvey Award recognizes exemplary faculty scholarship that reflects one of UNC’s top priorities. Its namesake is C. Felix Harvey, chairman of Harvey Enterprises & Affiliates and founder of the Little Bank Inc., both in Kinston. Harvey graduated in 1943 with a degree in commerce, and died in 2014 at the age of 93.

In 2007, along with his family, Harvey gave $2 million to endow the prize in acknowledgement of UNC’s significance to them and the important role Carolina has played in their lives. Members from five generations of Harveys have earned UNC degrees.

“Main Street, Carolina” created a flexible, web-based platform that allowed local organizations – libraries, schools, historical associations, among others – to build densely layered historical maps of their downtowns. Most of the Harvey Award funds went toward design of the software platform.

Out of that project came the Digital Innovation Lab, and specifically DH Press, the WordPress plug-in that is being used to create Digital Loray. DH Press is also open-source software, so it can be used by other organizations or projects both inside and outside the University.

Allen called the Harvey Award an example of how visionary philanthropy can make a transformative and long-lasting difference in the humanities. “The Harvey Award enabled me to make a leap at the same time I was creating a structure in which to make those kinds of leaps,” he said. “Funding like this means that our most innovative faculty in the humanities don’t have to rely only upon external funding to make research leaps possible.”

The Future

Digital Loray is a model that can be replicated in places all over the country. Allen said that he had been contacted by people at two Massachusetts mill projects to do just that.

“Theoretically, we could take this model to other mill villages and do much the same thing,” Gaddis said. “And, crucially, we are also showing that these kinds of partnerships between business and the university can extend to projects like this one and to the arts and humanities more broadly.”

Allen said dozens of students have benefitted from Digital Loray. He foresees scholars and the public researching other topics as the site grows and changes.

“This is the most exciting and energizing thing I’ve worked on in my 37 years at the University,” he said.

Video by Kristen Chavez ’13. Story by Susan Hudson and Claire Cusick. Photos by Dan Sears.