From left, doctoral student Femi Alabi and computer scientists Cynthia Sturton, Frederick P. Brooks Jr., Henry Fuchs, Montek Singh, Kevin Jeffay and Ron Alterovitz pose with computer equipment old and new, including Baxter (large robot) and Aldebaran Nao (small robot). (photo by Steve Exum)

Click on links at the bottom of this story for more articles on computer science.

Computer science research conducted at UNC has helped shape and guide technological advances, and it has played a critical role in propelling the Research Triangle region — and the state — into the Digital Age.

It all started in 1963 with a visit from computer scientist Frederick P. Brooks Jr., project manager for the revolutionary IBM System/360 family of computers.

Baxter is being programmed by UNC computer scientists, led by Ron Alterovitz, to assist people with tasks at work and at home. (photo by Steve Exum)

Brooks interviewed for a job running the campus computation center but decided he wasn’t interested in the position.

But the lecture he delivered as part of the interview process — “Ten Research Problems in Computer Science” — fueled the imaginations of a handful of campus leaders, including Southern literature professor and then-graduate school Dean C. Hugh Holman.

Holman and other campus leaders decided that UNC should form a department devoted to teaching and research in computer science, a field so young that scholars were still debating what it should be called.

The following year they asked Brooks back to lead the new venture. In 1964, UNC’s department of information science was born. It was the second computer science department (after Purdue University’s) in the nation.

This year, UNC’s computer science department is celebrating its 50th birthday, looking back over a half-century of high-tech changes that Holman, Brooks and others could not have imagined in the 1960s.

“You can’t think that far ahead,” said Brooks, Kenan Professor, who spent 20 years as department chair and still, in his 80s, teaches and advises graduate students. “Since I [became] interested in computers we’ve been through six technical revolutions. Who would have predicted the iPhone? Who would have predicted the Internet?”

Creating through collaboration

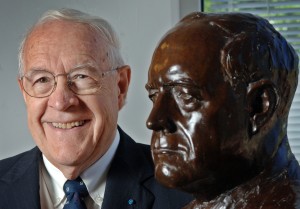

Fred Brooks poses with a bust made in his honor in Sitterson Hall. (photo by Dan Sears)

Many university computer science departments grew out of math departments or engineering schools. But Brooks and his fledgling department began as a stand-alone enterprise.

However, Brooks wasn’t interested in being separate from other academic disciplines. Instead, he and other early faculty programmed a culture of collaboration and interdisciplinary research into the department’s human operating system.

That cooperative approach reflected the warm welcome the department got at Carolina in the 1960s.

The statistics department helped fund the salary of a research assistant for Brooks. In 1966, the physics department allowed the installation of a graphics computer in one of its classrooms so it could be connected to the computation center directly below.

Brooks preached the “toolsmith concept” — the idea that computer scientists should be judged by how successful the hardware and software tools they’ve created are in helping people solve specific problems.

Brooks speaks at the dedication of Brooks Hall in 2008. (photo by Dan Sears)

Carolina faculty and alumni have helped design systems that aim radiation therapy at cancer tumors, create spellbinding special effects for films and help visually impaired children use computers, among many other examples.

Speeding forward

Graphics research has always been a focus at UNC. A department team developed the Pixel Planes computers in the 1980s, which at the time were the fastest graphics engines in the world.

But as computing technology has advanced, the problems faculty and graduate students tackle have changed, too.

“Computer science is inherently a very volatile field,” said Kevin Jeffay, the department’s current chair and Gillian Cell Distinguished Professor.

Now UNC is applying its graphics expertise to create virtual reality environments and help robots navigate in the real world.

“A key problem in robotics is to have an entity understand its relationship to its environment,” Jeffay said. “It’s all about building a model of the world … and graphics in its traditional form was about building a model of the world.”

UNC computer scientist Ming Lin advises graduate students. Her research interests include computer graphics, robotics and human-computer interaction. (photo by Dan Sears)

UNC computer scientists are also using that model-building paradigm to develop technology that produces “synthetic sound” — enabling a video game developer or movie special effects coordinator to tap a keyboard to get a desired noise, rather than creating and recording a real sound.

Other researchers are modeling the behavior of large crowds (useful for maintaining safety and security) and figuring out how to better secure modern computing systems. Throughout the department, Brooks’ emphasis on collaborating with those outside computer science remains a key focus.

Service to the state

UNC’s computer science department moved into Sitterson Hall in 1987.

Brooks’ belief in collaboration crossed institutional lines, as well. The UNC department has worked closely with Duke and NC State’s computer science units, as well as other schools, over the years. It also played a key role in North Carolina’s efforts to move from agriculture, textiles and furniture to a more technology-centered economy.

“One of the things the broader public might find interesting is really how much the history of the department is tied to the thriving and nurturing of other industries here,” Jeffay said.

In the late 1970s, state leaders tried to make North Carolina more attractive to technology companies. The Microelectronics Center of North Carolina (later renamed MCNC) was established to support computer science and microelectronics work across all the state’s universities.

“When Gov. [Jim] Hunt put in place the microelectronics initiative, we got a building 15 years earlier than we would have otherwise and we got five full professorships,” Brooks recalled.

In 1987, the department consolidated from several buildings into Sitterson Hall. In 2008, an addition was added and named for Brooks.

A cultural legacy

Doctoral student Femi Alabi is wearing Google Glass. As computer science celebrates its 50th anniversary, scientists are looking back over a half-century of high-tech changes. (photo by Steve Exum)

Despite all the technical accomplishments, the research and the new buildings, if you ask Brooks or other longtime faculty members what they are most proud of, they name people, not microprocessors or algorithms.

“I am very proud of all the doctoral students who have finished Ph.Ds under [my mentorship],” said Stephen Pizer, Kenan Professor, who came to the department in 1966, and has advised computer science students — and those in other fields, such as biomedical engineering.

UNC computer science alumni are working, teaching and conducting research at universities and companies across the country. Many alumni work at technology companies such as Google and Apple. Some have started their own companies. Others have won Academy Awards.

All of them are products of Brooks’ vision.

He had worked in a collaborative, cooperative environment at Harvard University when he earned his doctorate in applied mathematics. He found that same culture at IBM, where he worked for nine years before coming to Carolina. He wanted to create that spirit of collegiality in Chapel Hill.

Indeed perhaps his greatest engineering feat was replicating that culture at Carolina.

“It is inherently a friendly and cooperative enterprise,” Brooks said. “That’s the most important single thing.”

Read more about the computer science department’s anniversary celebration, which kicks off Oct. 18 and view the celebration schedule.

Watch a video about the department’s annual Maze Day celebration for visually impaired children.

[ By Mark Tosczak ]

More stories about computer science:

Brooks’ influence spans IBM mainframes to next-gen virtual reality

Medical imaging extends frontiers, aids diagnosis and treatment

Want to work in movies? Learn to code