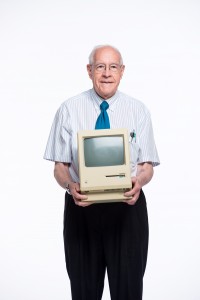

Fred Brooks holds a first-generation Mac. Signatures of the engineering team are molded into the inside of the plastic case. (photo by Steve Exum)

Click on links at the bottom of this story for more articles on computer science.

In 1944 a 13-year-old Fred Brooks sat in the public library in Greenville, N.C., and read about the Mark I computer in Time magazine.

The machine, created by Harvard University computing pioneer Howard Aiken and IBM, was designed to aid war efforts during the last part of World War II. It captured Brooks’ imagination.

“I was caught,” he recalled. At a time when the computer was still in its infancy, he knew that’s what he wanted to do with his life.

Brooks, who went on to found the UNC department of computer science 20 years later, earned a Ph.D. in applied mathematics at Harvard University, where he studied under Aiken, the Mark I architect. He then went to work at IBM, where he pioneered technology that we now take for granted.

Brooks also wrote the highly influential book The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering, originally published in 1975 and based on his experiences managing the legendary IBM System/360 project. He received a National Medal of Technology for that project.

A famous dictum from the book is now known as Brooks’ Law: “Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.”

Some have dubbed the book the bible of software engineering. In a 2005 Fortune magazine interview, Brooks said, “I would agree with that in one respect: that is, everybody quotes it, some people read it, and a few people follow it.”

His research at UNC has focused on real-time, 3-D computer graphics — virtual reality.

His work has helped biochemists study complex molecules and enabled architects to “walk through” buildings while they were still designing them, among other applications. He also has innovated in the use of haptic feedback (touch-based information) to supplement visual graphics.

It is work that today seems as cutting-edge and wonder-inspiring as the Mark I did in 1944.

“The wonder is still there,” Brooks said. “That’s why I’m still here.”

[ By Mark Tosczak ]

More stories about computer science:

Comp-Sci Turns 50: Breaking barriers from graphics to robotics

Medical imaging extends frontiers, aids diagnosis and treatment

Want to work in movies? Learn to code