The song “We Shall Overcome” is now known worldwide. How it came to be is a long story. In 1903 Reverend Charles Tindley had a big church in Philadelphia. He wrote a song that went, “I’ll overcome some day. I’ll overcome some day. If in my heart I do not yield, I’ll overcome some day.”

He put out a book called Gospel Pearls (1921) and started to use the phrase gospel music. Some of his students, like Lucie Campbell, became gospel songwriters. Somewhere between 1903 and 1945 “I’ll Overcome” got a quite different melody and a quite different rhythm. “I’ll overcome. I’ll overcome. I’ll overcome someday. If in my heart I do not yield, I’ll overcome someday.”

Some people say, “Deep in my heart, I do believe, I’ll overcome someday.”

It was a well-known gospel song in this fast version throughout North Carolina and South Carolina. In 1945 or 1946, 300 tobacco workers, mostly black and mostly women, went on strike in Charleston, South Carolina. People took turns on the picket line. Music-loving people are always going to sing. They sang hymns most of the time on the picket line. Once in a while they would sing a union song, but mostly they sang hymns.

Lucille Simmons loved to sing, “I’ll Overcome,” but she changed it to “We Will Overcome.”

She loved to sing it the slow way. You know, any hymn can be sung long meter or short meter. She liked to sing “We Will Overcome” in long meter. She had a beautiful voice, and they said, “Oh, here is Lucille. We are going to hear that long, slow song.”

She would sing it, “We will overcome. / We will overcome. … / We’ll get higher wages. … / We’ll get shorter hours.”

Zilphia Horton, a white woman, was an organizer from the Highlander Folk School. She comes down to help, and she is completely captivated by this song. Zilphia had a lovely alto voice and an accordion. She taught the song to me on one of her fundraising trips up North. I liked it. I found myself singing it and teaching it to audiences. “We will overcome. / We will overcome.”

I added some verses. “We shall live in peace, / the whole wide world around. … / We will walk hand in hand.”

I added some verses. “We shall live in peace, / the whole wide world around. … / We will walk hand in hand.”

Out in Los Angeles, I met a young fellow named Guy Carawan, and I taught it to him. Guy Carawan’s family had come from North Carolina. He wanted to get acquainted with the South, as I had done. Next thing you know, he was helping the Highlander Folk School with workshops. In 1960, they had an all-South workshop on the use of music in the freedom movement at the Highlander Center. So Guy sings this song. He gave it the Motown beat, the famous soul beat.

I had changed the “will” to “shall” — me and my Harvard education. “We shall.” I think it opens up the mouth better, and we changed the rhythm. “We shall overcome. / We shall overcome.”

Within one month, it spread through the South. It was the favorite song at the founding convention of SNCC three weeks later in April 1960 in Raleigh, North Carolina, where people came from all through the South.

Dr. King heard me sing the song three or four years before. He came to the Highlander Center, and Miles Horton, Zilphia’s husband, says, “Pete, won’t you come down and lead some songs. We can’t have a gathering here without music.”

I sang “We Shall Overcome.” Anne Braden later told me that she drove Dr. King to Kentucky the next day and remembers King in the back seat saying, “‘We shall overcome.’ That song really sticks with you, doesn’t it?”

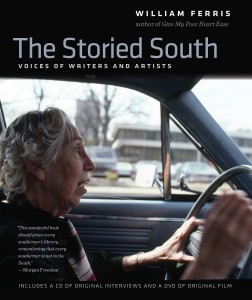

An interview with Pete Seeger excerpted with permission from The Storied South: Voices of Writers and Artists by William Ferris, the Joel R. Williamson Eminent Professor of History and senior associate director of the Center for the Study of the American South. Copyright © 2013 by William Ferris. Published by the University of North Carolina Press, www.uncpress.unc.edu. The book includes a companion CD and DVD.