Silvia Tomaskova spent 2010 to 2011 in South Africa studying prehistoric rock art. (photo courtesy of Silvia Tomaskova)

UNC anthropologist Silvia Tomášková spent 2010 to 2011 in South Africa studying prehistoric rock art drawings as part of the research for her book, Wayward Shamans: The Prehistory of an Idea. She then returned to Carolina with a fresh perspective on the drawings, eager to share this knowledge with students in a new course involving interactive learning techniques.

She wanted to trace the origins of shamans (sometimes described as proto-priests, religious leaders, artists and healers) from Siberia to South Africa and to examine their gendered interpretations. (They are often depicted as men.) For the last 20 years, scholars had drawn from 19th century ethnographies to propose that the South Africa rock art drawings were done by shamans under ritualistic trance. Tomášková wanted to see the drawings for herself.

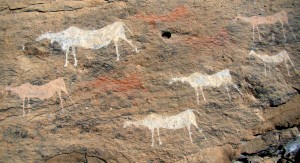

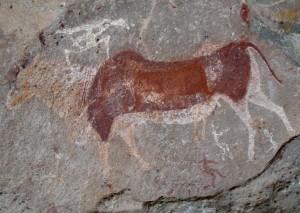

South Africa has one of the largest collections of painted rock surfaces in the world; the Rock Art Research Institute in Johannesburg estimates there are about 2 million of the colorful images. The art, primarily painted by the indigenous San people and their ancestors, dates anywhere from 500 to 10,000 years old.

Tomášková, an associate professor of women’s and gender studies and anthropology, received an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation New Directions Fellowship to support her research. The prestigious awards are given to top scholars in the humanities to work on new problems and to acquire different skills outside their disciplines.

Tomaskova received a Mellon New Directions Fellowship to support her research. (photo by Beth Lawrence)Her interest in South Africa traces back to 1981 during the Cold War, when she was living in Czechoslovakia (today the Czech Republic). At the time, Eastern European political refugees were accepted by a limited number of countries, including Australia, Canada and South Africa. Tomášková headed to Canada, then later to the United States for graduate school.

“I considered South Africa the strangest offer because I would be going from one totalitarian regime to another,” Tomášková said. “This was still under apartheid so I had no desire to go to South Africa, but the parallels between communism and apartheid were very striking to me.

“With the New Directions Fellowship, which allows you to go in a new direction geographically and theoretically, I thought this was my chance to connect the two, Eastern Europe and South Africa.”

Field work deep in the mountains

While in South Africa, Tomášková taught at the University of Cape Town and became immersed in the country’s cultural, political and environmental diversity.

She joined the Archaeological Society of South Africa and participated in field surveys in the Cederberg and Drakensberg Mountains. The rock art drawings are found in remote locations and are difficult to access, sometimes requiring a two-to-three-day drive inland, then two to three hours of hiking. Art seekers might have to climb steep slopes or walk through long, narrow valleys to reach the images.

Tomaskova’s book challenges the notion that the rock art drawings were down by shamans under hallucinogenic trance.

The drawings are often hidden under rock shelters, and they are very colorful — created with a palate of ground powders like red ochre. Animals are the most common theme (with the antelope the most popular animal), and the drawings are often associated with water.

“I am very much an outdoors person, and the landscape is just so beautiful,” said Tomášková, who took hundreds of photographs of the drawings, including the one featured on the cover of her book. “What’s interesting is there is plenty of rock surface … but the images are literally one on top of another in this small area. Many of the drawings are layered on top of each other, so I think there’s a conversation over time going on between the images, even though they may be 200 years apart.”

Seeing the art in person helped her to view it in a more nuanced way and to challenge the notion that the drawings were all done by shamans under hallucinogenic trance.

“I think there are some [examples] of ritual performances, but there are many, many other images that I am absolutely convinced have nothing to do with shamanic ritual,” she said.

In Wayward Shamans, Tomášková argues that she did not set out to evaluate or critique such claims.

“My interest in shamans has always been in their history and geography — their invention as an idea and their global travels on the wings of imagination,” she wrote.

Using her research in teaching

Tomášková brought her research on South African rock art into a new undergraduate prehistoric art class of 120 students that she taught for the first time in spring 2013.

She received a “100+ Large Course Redesign Grant” from the UNC Center for Faculty Excellence to rework the class for spring 2014. The grants are given to faculty members to implement changes to large enrollment classes in order to improve student engagement and learning outcomes.

She took steps toward making the big class seem small by working with The Ackland Art Museum to set up a teaching gallery, where small discussion sections of 20 students were held.

Tomášková hopes to continue her work with The Ackland, for which she received an additional course development grant. She’ll find ways to make the class even more interactive, possibly setting up an online gallery, where students could examine “how art is made, and how do we communicate art to people?”

Exploring the ‘Cinderella of rock art’

While in South Africa for the New Directions Fellowship, Tomášková learned about another form of rock art that is less glamorous and understood than the colorful drawings —engravings that are etched and carved into stone, also by the San people.

She calls the engravings, which are often not representations of actual objects but geometric patterns and shapes, “the Cinderella of rock art.”

When seasonal waters recede, people would sometimes carve slabs of stone that would then become covered by water again, giving them an additional polish.

“They are gray and much less attention-grabbing,” she said. “They are patterns or shapes, and often times on the ground or a wall. They are much more discrete, and I’ve always been the champion of the underdog.”

She decided to take her research in a new, but related direction.

She applied for a “post-award research project,” which Mellon also funded. She returned to South Africa in the summer of 2013 and will be there again in summer 2014 to map the images. Her original training as an archaeologist was in stone tool analysis, and Tomášková said she considers stone tools a form of art.

Tomaskova will work with local archaeologists and indigenous communities in South Africa on issues of heritage tourism. (photo by Silvia Tomaskova)

Working with computer scientists (she has received help from UNC’s Anselmo Lastro), she hopes to develop a 3-D archive of the engravings, possibly expanding her research into a digital humanities project. New technology will allow her to examine if the engravings have been changed or modified.

“Did people come back and make corrections?” she said. “The 3D image allows you to see the sequence of production over time. Someone may have added to it. Maybe the piece of art was not an individual product; it may have been made by a group of people.”

Tomášková will also work with local archaeologists and indigenous communities to explore the issue of rights and ownership regarding ancient landscapes. It’s an area South Africans are interested in, but they are taking a cautious approach. In one community, for example, a local guide has been trained to take tourists to see examples of rock art.

“We have a concern as archaeologists about how our work connects with the community,” she said. “This is their heritage, and they need to be the ones to choose what they want the public to see.”

Silvia Tomaskova received a 2013 Carolina Women’s Leadership Council award for her work in mentoring junior faculty. She also directs UNC’s Women in Science Program.

[ Story by Kim Weaver Spurr ’88 ]