Click on links at the bottom of this story for more articles on the Center for the Study of the American South.

While studying for a UNC master’s degree in folklore, Elijah Gaddis became interested in the relationship between land and the people who work on it. This fascination took him to Caledonia Prison Farm near Tillery in Halifax County, N.C.

Gaddis was among the graduate students who received grants for research projects from the Center for the Study of the American South (CSAS) in summer 2012. His study focused on the prison farm’s plantation history in Halifax County, one of the richest counties in the state before the Civil War, and now among the poorest.

“The prison farm drew me there,” said Gaddis, who is now a Ph.D. student in American studies. “How did this plantation become a prison? It’s in the midst of where residents live. How did they live around it? ”

First Gaddis studied the area’s history through archives and state records. He learned that Halifax County, which dates back more than 300 years, was home to many plantations along the Roanoke River. Early Scottish settlers included Samuel Johnston, whose family owned several plantations. The largest was Caledonia, the Latin word for Scotland. Hundreds of slaves farmed tobacco and other crops on Caledonia’s thousands of acres. After the Civil War, the land eventually passed to the plantation overseer, Henry Futrell. Many former slaves continued to work on the land in exchange for shelter, food and modest pay.

In 1891, Caledonia was sold to the state of North Carolina to become a prison farm. The property continued to produce tobacco and other crops on 4,500 acres. In the 1920s, Caledonia held a third of North Carolina’s prisoners; today the prison farm houses about 300 inmates.

Approximately 5,500 acres of land at Caledonia Prison Farm are under cultivation today, according to Keith Acree, spokesperson with the N.C. Department of Public Safety.

“Managed by Correction Enterprises, the prison farm includes chickens, corn, wheat and soybeans,” he said. The inmates also farm 300 acres of tomatoes, sweet corn, collard greens, sweet potatoes, squash, cucumbers and melons. In addition, inmates work in the prison’s 12,770-square-foot cannery, which preserves crops, fruit juices and concentrated tea that is sent to prison kitchens across the state.

“The facility has the capability of canning about 500,000 gallons of vegetables a year,” Acree said.

When Gaddis first visited the town of Tillery near Caledonia, he discovered a strong history of activism.

“Residents of Tillery formed one of the first chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in eastern North Carolina,” he said.

For six months Gaddis interviewed residents in the close-knit community.

“The African American experience with farming is burdened by hundreds of years of exploitative labor, first as slaves and then as sharecroppers,” said Gaddis. “This relationship is a mixture of pride in ownership and determination to not allow institutional forces to repeat patterns of injustice.”

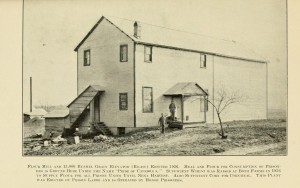

The flour mill and 15,000 bushel grain elevator at Caledonia Prison Farm, circa 1926. Meal and flour ground under the name “Pride of Caledonia.” (photo courtesy of archive.org)

One modern issue for many African American farmers was losing land through foreclosure. A 1999 class action law suit, Pigford vs. the U.S. Department of Agriculture, alleged racial discrimination through farm loans between 1983 and 1997. A settlement of almost a billion dollars has been paid or credited to more than 13,300 farmers, one of the largest civil rights settlements in history. The 2008 Farm Bill allowed additional claims to be heard, and in 2010 Congress appropriated another $1.2 billion to claimants in what is referred to as Pigford II.

Gaddis said his research on Caledonia Prison Farm and the surrounding community helped him to understand the people of the area and their complex history.

Summer 2013 graduate student grant recipients undertook projects that included housing practices in Durham County, the Voter Education Project, labor feminism, religion and native people, Latino immigration, Creoles of color in 19th century New Orleans, photojournalism in the Cherokee Nation and more. They will present their research at a poster session Sept. 20 at the Love House and Hutchins Forum.

[Story by Eleanor Lee Yates ’78 ]

More stories about the Center for the Study of the American South:

Front Porch Portal: Home for Southern research celebrates 20 years

Pete Seeger Remembers, an excerpt from Bill Ferris’ new book

Southern Cultures: Journal covers it all, from tobacco queens to blues music

Preserving the Voices: Southern Oral History Program celebrates 40 years

Leading the Southern Oral History Program